“People who have exclusively shopped in-store are making their first online purchases out of pure necessity, and even more are making their primary shopping channel online.” – Taylor Sicard.

In the 25 plus years I’ve worked in marketing, there’s never been a year like 2020. Since March, the pandemic has touched virtually every aspect of Americans’ shopping behavior. It has affected how and where we shop and what we buy (and don’t buy). These vast changes have happened in a very short time.

In the weeks after the pandemic hit, for example, virtually overnight, Americans stopped shopping for pretty much everything except groceries. There was an unprecedented 40 percent drop in spending, most of it on discretionary purchases. Because of this pause, consumers’ savings rates shot up temporarily. These spending and saving patterns have reversed since then, but other shopping patterns have continued to evolve.

Some changes in pandemic-induced consumer behaviors are entirely new and unexpected, quantum jumps, so to speak. Others are swift accelerations of gradual trends that had been occurring for years and even decades before the pandemic.

In this blog post, I want to explore three of the most significant shifts in the shopping behavior of Americans in the months since March because of the pandemic. No one could have predicted these trends at the beginning of 2020.

1) The shift from physical shopping to online shopping

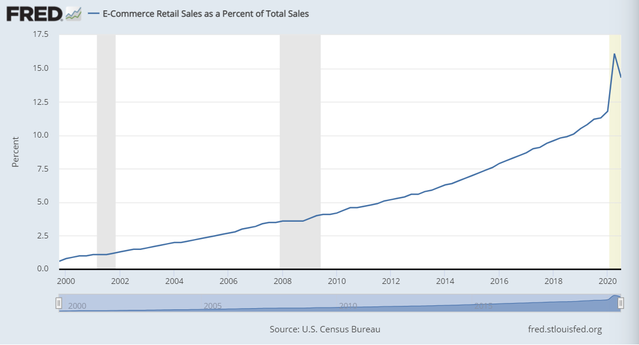

There are obvious advantages to buying products online, such as perceptions of lower prices, more choices, and greater convenience. In the two previous two decades, however, e-commerce had managed to garner less than 15 percent of total shopping dollars. Not only that, going into 2020, it was expected to increase gradually, by about 1 percent every year until 2024.

By and large, marketers believe that physical shopping has distinct advantages that can’t be replicated online. Whether it’s a television, a mattress, a jacket, or something else, examining a tangible item virtually on a screen is inferior to seeing it in person, inspecting its heft, texture, and tangible qualities, experiencing the performance, and so on. The firsthand aspects of physical shopping are unique and irreplaceable.

However, the pandemic dramatically accelerated the gradual upward trend of e-commerce (see the graphic below from the St. Louis Fed). According to one analysis, “the pandemic has accelerated the shift away from physical stores to digital shopping by roughly five years.” The reasons have less to do with lower prices or greater convenience and more to do with safety and distance. At the moment, physical shopping is potentially hazardous to our health.

2) The shift from services produced by employees to services produced by customers

In services marketing, we distinguish between full-service offerings that are entirely or mostly produced by service employees and ones that are co-produced or DIY services. These latter services are common and are predominantly produced by customers themselves. For example, you can go to a restaurant and have the meal prepared and served to you, or you can order the food to-go with curbside delivery or have it delivered. The sit-down restaurant meal is a full service, but the picked-up or delivered meal is a co-produced service because you will have to re-heat the meal at home, serve it, clean up after eating, dispose of the packaging, etc.

Broadly speaking, the Covid-19 pandemic has taken a dreadful toll on full services, and it’s been a boon to DIY and co-produced services. While fine dining restaurants, apparel retailers, department stores, and other full services have been struggling to survive, sellers that support DIY activities like Home Depot and Lowe’s, and those that allow consumers to do more activities at home like Dick’s Sporting Goods and Best Buy have been thriving. Everyone from doctors, veterinarians, gyms, and even restaurants have been focused on how to offer co-produced services that customers can utilize at home.

In a nutshell, American consumers are playing much bigger roles in creating services themselves during the pandemic that they relied on others to perform before.

3) The shift from experiential in-person services to virtual services

A third, and perhaps the most drastic shift of the three, is the migration of consumers away from services that are highly experiential and are partaken in person to services that are virtual and partaken at home. The industries worst-hit by the pandemic are experiential service industries. Among others, these include hotels, cruise lines, airlines, theme parks, and personal care. They sell in-person services where the experiential aspects provide the main benefits to customers. In contrast, the beneficiaries are services like video games, videoconferencing, and home gyms, which provide experiential services virtually, or in consumers’ homes.

I experienced this shift myself as a higher education worker. Instead of teaching my university classes physically with all students in the classroom, I taught this fall using a “dual-delivery” method where more than half of my students attended classes virtually. Only a handful of students were physically present. (Higher education has been impacted significantly in good and bad ways, but that’s a topic that deserves its own post).

Will the end of social distancing reverse these shifts?

These shifts in Americans’ shopping behavior can be attributed to mostly the same reasons: the perils of physical contact, the desire for socially distancing, and the preference for staying at home.

Shopping behaviors that require interaction with other humans who may be potentially infected with the Covid-19 virus appear risky to many of us. The greater the likelihood of close contact with other people (employees or other customers), the greater is the risk. Shopping online, performing more aspects of the service ourselves, and bringing experiential services into our homes via virtual technologies allow us to obtain most of the same benefits while maintaining safe social distance. Situationally, these shifts allow us to avoid the stress of encountering those who refuse to wear masks, having to use new, cumbersome, and inferior buying procedures, having to pay more to cover Covid-19 surcharges, and so on.

For all three shifts in consumer behavior I’ve described, the behaviors that we are shifting to are not necessarily superior to the behaviors we are shifting away from. The socially distant, in-home, virtual shopping and consumption experience is inferior in many ways to its physical, full service, experiential counterpart. It is not at all clear, then, whether these three Covid-19-driven shifts in shopping are here to stay. Most Americans may well revert to their previous, pre-pandemic shopping habits in a year or two when the fear and the risks associated with Covid-10 have dissipated.

"behavior" - Google News

November 30, 2020 at 09:46PM

https://ift.tt/2KP2sdL

3 Ways Shopping Behavior Has Changed During the Pandemic - Psychology Today

"behavior" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2We9Kdi

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "3 Ways Shopping Behavior Has Changed During the Pandemic - Psychology Today"

Post a Comment