Paramount Theater in Seattle

Source: Wikimedia Creative Commons/ SounderBruce

Over the last several months, the world has experienced unprecedented change: bushfires in Australia, an international pandemic and now global protests against police brutality. With the onset of the coronavirus, COVID-19, our lives have changed drastically. In addition to grieving loved ones and loss of employment, we have also had to adopt new social behaviors such as wearing masks in public, staying home, and not seeing family and friends. The physical isolation that this pandemic requires has exacerbated the mental burden that many are experiencing during these difficult times. The toll of the pandemic on the psyche of the individual has been enormous.

As a behavioral scientist, I was admittedly skeptical that people would make the changes necessary to “flatten the curve”. Time and time again, the world cries for collective action and humans (particularly those in developed nations, including the U.S.) fail to enact meaningful change. Climate change is the most obvious example, with millions suffering globally, and yet little action is taken to address or alleviate the issue. Likewise, Black Americans have long been suffering from police violence and brutality but little change has occurred in recent years despite the many high-profile killings of Black men and women by police in the past decade.

Unlike climate change and past attempts at police reform, the pandemic sparked widespread behavior change within weeks. Why did the majority of Americans adapt their behaviors to wear masks and not see loved ones, and what lessons from the pandemic can we utilize to provoke collective change in other difficult situations? Bold, innovative action by a few state and local leaders was essential for propelling national action. However, the psychological motivations of staying home during the pandemic were fundamental: people experienced grave fear for their own health and safety.

Swift local leadership sets a national trend

As a Washingtonian raised in the city of Kirkland (most popularly known as the home of the beloved Costco but unfortunately also the first epicenter for U.S. COVID-19 cases), I began hearing about the virus from family and friends. My mom and grandma lamented the unfolding events and felt isolated by the lack of national understanding and attention as the situation worsened. Despite the fact that this virus outbreak was a mile away from my childhood home, exploding at the very same nursing home where my grandma had previously recovered from several surgeries, I was arguably naïve. I recall feeling like coronavirus was a Seattle problem and not something that would affect me 2,000 miles away in my current home of Madison, Wisconsin.

Washington State Governor Jay Inslee was the first elected official to navigate the unknown waters of COVID-19. On February 29, Inslee declared a State of Emergency in Washington. A mere 10 days later, on March 9, my alma mater, the University of Washington (home of 46,000 students) and former school district, Northshore (23,000 students in K-12) announced that all classes would move online. After two weeks of asking people to quarantine with mixed results, on March 15, Inslee closed all bars and restaurants, canceled school, and begged people to stay at home. I give you this timeline to help convey the rapid changes that were taking place in everyone’s life.

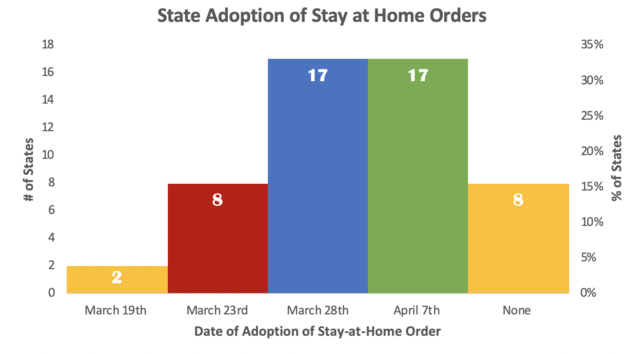

After Washington’s mandates to close schools, offices, restaurants, and other social gathering spaces, Puerto Rico was the first State or territory to implement a formal Stay-at-Home order, on March 15. While Washington and Puerto Rico were ahead of the curve, however, it wasn’t until California implemented its Stay-at-Home order on March 19 that more states followed suit. California was an early adopter that expedited the spread of Shelter-in-Place legislation across the U.S.

So, what drove this quick adherence to massive behavior change?

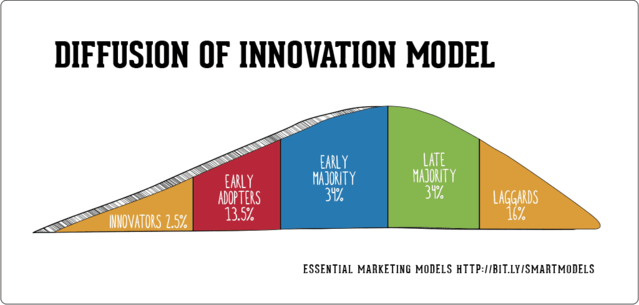

Diffusion of Innovation Model

Source: Used with permission from Smart Insights

Though there are many theories to explain the behavior change, for this context I find the Diffusion of Innovation Model and Theory (Rogers, 1961) particularly helpful for understanding the adoption of Shelter-in-Place orders. The general idea is that a new behavior/idea is not embraced by an entire society simultaneously. Rather, diffusion through a population is a process whereby a very small group of people implement a new idea/behavior followed by a slightly bigger subset of people adopting these ideas or behaviors. This behavior then diffuses through the society before it becomes a social norm. The NGO, Rare, has a great animated video explaining this theory.

I was very skeptical that mass change would sweep the U.S. I pessimistically thought that these orders wouldn’t provoke change because they didn’t have teeth (unlike in France). I am sure I am not alone when I say the first weeks of the pandemic felt like 100 years. There was so much fear and uncertainty. Everything was rapidly changing, and contradictory information was being released daily. People were adapting to working and learning from home and making huge lifestyle changes to accommodate the “new normal.”

But as state after state implemented Stay-at-Home orders, I was relieved to be proven wrong. It took 24 days for 42 states, plus Puerto Rico and DC, to implement Stay-at-Home orders. Only eight states refused to act. Nonetheless, in a republic with 50 states plus several territories, 44 Stay-at-Home orders is remarkable. Using data from The New York Times, I graphed the adoption of Stay-at-Home orders in the US. The pattern is in fact strikingly similar to the Diffusion of Innovation Model!

Source: Sophia Winkler-Schor created with data from NYT Research

The power and importance of communication science

In addition to changing laws, we need to change people’s behavior. Scientifically informed behavior change and communication can make a world of difference. While the U.S. is by no means a stellar example of an effective national coronavirus response, some states were. The language used by governments such as “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” instead of Shelter-in-Place, which evokes panic, and the little yellow lines many stores are using to prompt people to keep two meters' distance are just a few examples of how behavioral and communication scientists' input have likely helped flatten the curve. In particular, message framing (the focus of the message), targeted messaging (who the message is geared towards) and nudging (small structural changes to cue behavior) can be effective in achieving behavior change goals.

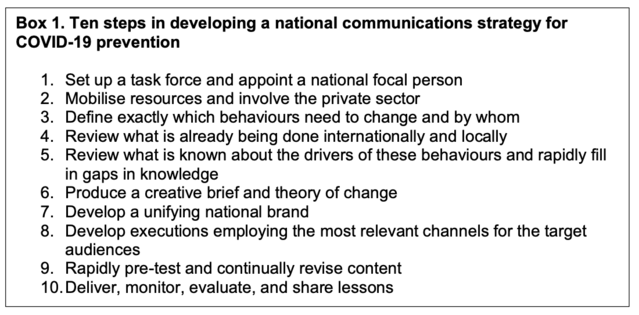

Instead of using language that sounds scary and impinges on the American value of freedom, slogans such as those used in Michigan—“Stay Home. Stay Safe. Save Lives.”—convey that you personally will be safer at home but also make you feel good because you are saving lives. This catchy name took hold and subsequent states also adopted similar campaign slogans. In response to the pandemic, Curtis et al. (2020) provided a 10-step plan for governments to develop science-based communication strategies for effective behavior change. The integration of science both from public health and communication experts will increase the likelihood of creating sweeping societal behavior change.

Source: Source: Curtis et al. (2020)

Achieving behavioral tipping points

To induce widespread behavior change, a “tipping point” must be reached. Grounded in the Theory of Critical Mass, a behavioral tipping point is the threshold at which a behavior is well on its way to becoming a social norm (Centola et al. 2018). In relation to Diffusion of Innovation, this is often identified as the stage between Early Adopters and Early Majority. Though the threshold varies based on the behavior (it's estimated to be between 10-40%; ibid.), you don’t need a majority of the population to reach the behavioral tipping point. Three weeks after Washington declared a State of Emergency, nine states had adopted Stay-at-Home Orders. It only took another week for that number to rise to 30 states. For COVID-19, the tipping point seems to have been roughly 18% of states.

As early innovators, the local and state government in Washington, as well as schools and companies, rang the alarm bells that helped ignite the widespread changes we saw across the US. The pandemic has demonstrated just how powerful state government can be for achieving this behavioral tipping point. The changes the U.S. experienced in the past few months have been astounding. Watching not only the U.S. but also the world adapt to the pandemic proved to me that massive structural changes can happen quickly with strong local leadership and a motivated public.

Though COVID-19 is a global problem, like many other issues, it shows the value of acute local action. Local and state governments need to take a strong stance on issues that affect their constituents and consult with communication experts to identify the most effective methods for tailoring information to encourage change. However, we as citizens also have the power to exert more pressure on our local communities. The science backing climate change is undeniable, yet government and corporate action is pitiful. It is safe to say that climate change has had a pretty bad PR team (which I will delve into further in the next post).

It can be difficult for individuals to understand why formidable problems like climate change are relevant on the local level—we often lack the direct experience necessary to cue to our brains that danger is brewing (Gifford, 2011). This is where experts in social marketing can help. Through framing campaigns to make them personally relevant to persuadable pockets of the population, change can take hold and grow more quickly and organically. As Vladimir Lenin said, “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.”

In the next post, I want to explore how we can apply the knowledge gleaned from the pandemic response to behavior change campaigns about other societal issues, such as climate change and police brutality.

"behavior" - Google News

June 11, 2020 at 10:48PM

https://ift.tt/3fbMioP

At The Tipping Point: Behavior Change Lessons From COVID-19 - Psychology Today

"behavior" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2We9Kdi

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "At The Tipping Point: Behavior Change Lessons From COVID-19 - Psychology Today"

Post a Comment