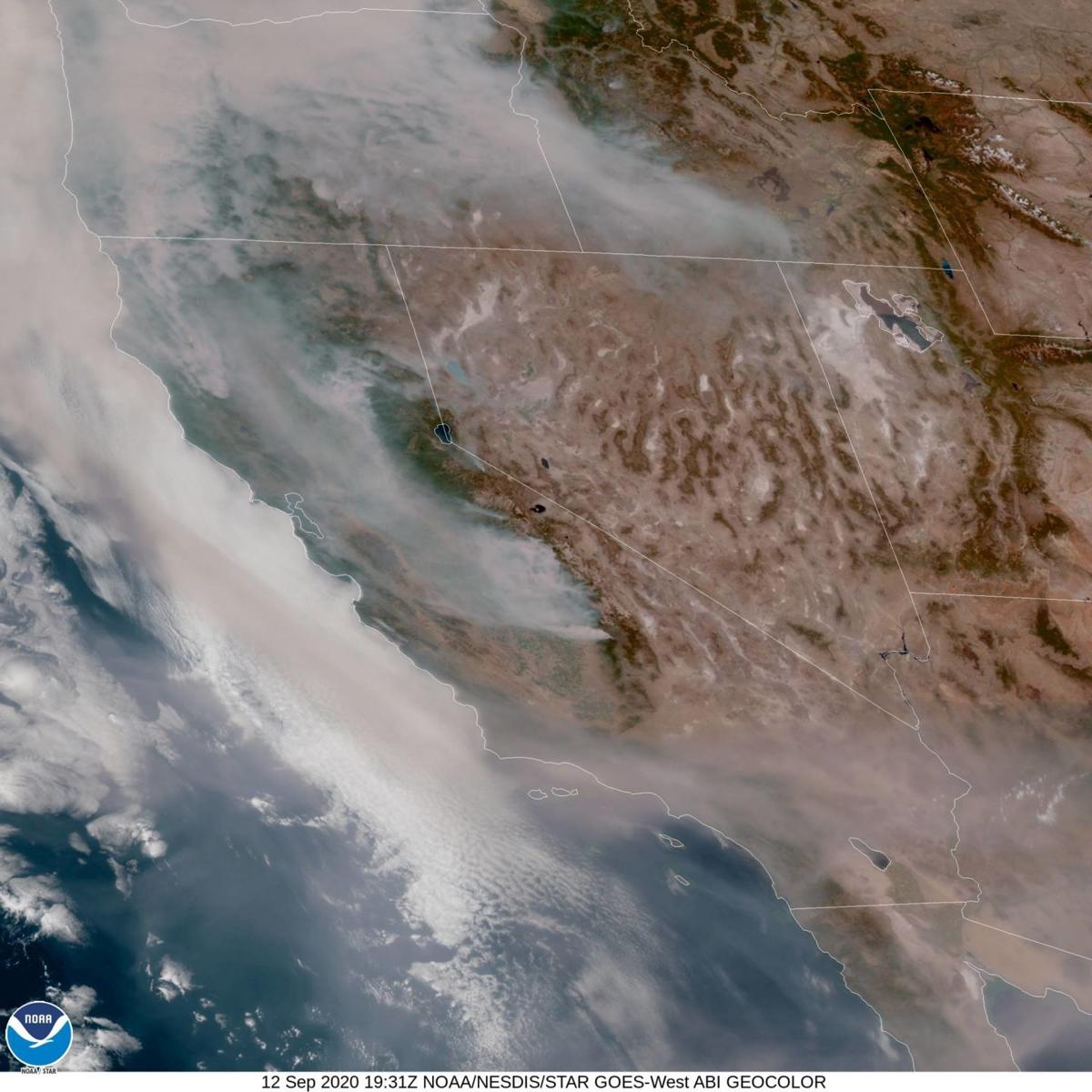

A GOES-West satellite image of the West Coast where there is less smoke today than most of last week.

Last week, different conditions came together to create the worst outbreak of wildfires California and Oregon have seen up to this point in time.

As any firefighter will tell you, three ingredients are needed to have a fire — heat, oxygen, and fuel — "the fire triangle."

A heat source such as a spark from a trailer chain hitting the highway can ignite a fire, but the heat also preheats the fuel in the fire's path, allowing it to spread faster. Mid-August and early September have seen unprecedented heat. Last Sunday, Sept. 6, temperatures hit a Death Valley-like 122 degrees in Solvang, Cal Poly reached 120 degrees, the previous record for the campus that stood for many years was 112 degrees, which occurred in Sept. 1971. The San Luis Obispo, Paso Robles, and Santa Ynez airports all reported a high 117 degrees!

In the future, the oceans and atmosphere will continue to warm due to climate change. As I wrote last week, I reviewed the record high and low-temperature data for September at the Paso Robles Airport. In the current data set listed by the NWS on their website (https://www.weather.gov/lox/), weather observations at the airport stretch back to 1948. Even though there are 52 years of temperature data from the 1900s versus only 20 years in the 2000s, there are already 17 high-temperature records set in this century. In the next 30 years, will all the high-temperature record marks at the airport occur in this century?

Easterly winds of 20 and 30 mph with gusts of 50 plus mph--some of the mountains in Northern California saw winds gusts as high as 66 mph-- were reported last Monday into Tuesday. These winds not only provided plenty of oxygen for the fires to thrive but also drove them across the state's topography at frighteningly high speeds. The long-range climate models continue to point out that wind events will become stronger in the future.

This summer's heat has dramatically lowered vegetation's moisture content or as firefighters refer to as fuels. To make matters worse, massive amounts of born-dry vegetation and millions of bark beetle-infested dying, or dead trees have been allowed to accumulate over decades. Record amounts of CO2 in our atmosphere will enable some foliage types, like the Toxicodendron family of plants that encompasses poison oak, Ivy, and Sumac, to grow faster during the rainy season, adding more fuel to potential fires.

These conditions last week combined to create extreme fire behavior. In other words, a catastrophe.

The great mid-August lightning storms sparked hundreds of wildfires throughout Central and Northern California; a few of these gigantic fire complexes were still burning when the early September heat wave and wind event arrived. These fires are now some of the biggest the Golden State has ever seen.

In fact, 6 of the top 20 most massive wildfires in California history have occurred this year. The "August Complex" fire currently burning in the Coast Range of Northern California has grown to around three-quarters of a million acres and is now the biggest in state history. Over 3 million acres have burned this year, besting the previous record of 2 million acres set in 2018.

The smoke from the mid-August fires up to that point was the most persistent I have even seen; this week, it was worst. The think opaque layer of this sickly looking tan smoke is so bad; it has thrown many of the numerical weather models output off, which meteorologists use as guidance to forecast the weather.

I'm concerned that massive amounts of flooding and erosions could happen if heavy rains fall in the fire-scarred areas.

With the threat of wildfires increasing, many homeowners throughout the state have difficulty keeping or finding fire insurance, especially those living in higher fire-threat areas. You can find the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) Fire-Threat Maps at https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/firethreatmaps/ to see if you live in Tier 2-Elevated or Tier 3-Extreme location. You may be surprised by how much of the state is located in these areas.

Next week's column, I will speak with fire behavior experts and report their recommendations for the best course of action to deal with this tragic situation.

What is a public safety shutoff?

High temperatures, extreme dryness and record-high winds have created conditions in our state where any spark at the wrong time and place can lead to a major wildfire.

If severe weather threatens a portion of the electric system, it may be necessary for PG&E to turn off electricity in the interest of public safety. This is known as a public safety power shutoff (PSPS). The PSPS events in 2019 disrupted many of our customers’ lives. We learned from last year’s events.

This year, PSPS events, if needed, should be smaller in size, shorter in duration and smarter for our customers. To lean more, please visit www.pge.com and view the video “PSPS – What’s New in 2020?”

John Lindsey is Pacific Gas and Electric Co.’s Diablo Canyon Power Plant marine meteorologist and a media relations representative. Email him at pgeweather@pge.com or follow him on Twitter @PGE_John.

Subscribe to our Daily Headlines newsletter.

"behavior" - Google News

September 13, 2020 at 09:30PM

https://ift.tt/3kazRvS

Lindsey: Last week's conditions combined to create extreme fire behavior - Santa Maria Times

"behavior" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2We9Kdi

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Lindsey: Last week's conditions combined to create extreme fire behavior - Santa Maria Times"

Post a Comment